What Have PostgreSQL Functions Ever Done for Us?

So, in all seriousness - what have PostgreSQL functions and stored procedures ever done for us?

In 2026, we have ORMs, microservices, serverless functions, GraphQL, and AI writing our code. Who needs stored procedures anymore? They're relics of the past, right?

Wrong.

As a general rule, every single command or query for application use - I always wrap up in a PostgreSQL user-defined function. Sometimes it's a stored procedure when I need fine-grained transaction handling, but that's rare. It's mostly functions for the majority of cases.

To use OOP terminology - they are my data contracts. The formal agreements for data exchange between PostgreSQL and application instances:

- Function parameters = input data contracts

- Function results = output data contracts

Functions encapsulate commands, queries, and table access. Those are private parts. Data contracts are public. They do not change unless the application changes too.

And with tools like NpgsqlRest, these functions become REST API endpoints automatically - the foundation of a radically simpler, faster, and more secure architecture.

Let me show you with a real-world example.

A Real-World Story: The Function That Evolved

Suppose we have this big table in a legacy system:

sql

create table device_measurements (

id bigint not null generated always as identity primary key,

device_id int not null references devices(device_id),

timestamp timestamp not null,

value numeric not null

);Standard ORM-generated table with an auto-generated integer primary key. There are indexes on device_id and timestamp.

Now, this legacy application runs thousands of queries like this for analytical reporting:

sql

select "timestamp", device_id, value

from device_measurements

where device_id = $1

order by id desc

limit 1;When an application runs the same query repeatedly with different parameters, that's a code smell. It's very likely the N+1 antipattern at work - parameter values fetched from one query, then another query for each result. This makes the entire application slow and sluggish.

But resolving N+1 antipatterns requires careful analysis and a full rewrite - a luxury not every legacy system can afford. Sluggish is still usable.

Step 1: Extract the data contract

What's the intention? Return the latest device measurement - the one record that was last inserted.

- Input: device_id (integer)

- Output: single record with timestamp, device_id, value

sql

create or replace function get_latest_device_measurement(_device_id integer)

returns table (

"timestamp" timestamp,

device_id integer,

value double precision

)

security definer

language sql as

$$

select "timestamp", device_id, value

from device_measurements

where device_id = _device_id

order by id desc

limit 1;

$$;The name clearly describes the intention. Parameters and return type define the contract.

Now replace the query in the application:

sql

select "timestamp", device_id, value from get_latest_device_measurement($1)This makes data access readable and maintainable. It's Clean Code for SQL - Uncle Bob would be proud.

Performance-wise, we didn't change anything. Yet. But we made the application infinitely more maintainable.

As time goes on, data grows. Who could have predicted that?

The decision was made to migrate to TimescaleDB and partition this table on the timestamp field.

TimescaleDB partitions don't allow unique indexes on fields not used for partitioning. The primary key on id had to be dropped.

Our function relied on ordering by that primary key index. Dropping it made reporting unusable.

Luckily, functions can be changed atomically - no downtime, no application change:

sql

create or replace function get_latest_device_measurement(_device_id integer)

returns table (

"timestamp" timestamp,

device_id integer,

value double precision

)

security definer

language sql as

$$

select "timestamp", device_id, value

from device_measurements

where device_id = _device_id

order by "timestamp" desc

limit 1;

$$;That worked fine. Right index used, a few partitions, reports usable again.

As time goes on, data grows. Again!

Although this version used indexes, it had to scan each partition separately. As partitions grew, reporting became unusable again.

New strategy - add a composite index:

sql

create index on device_measurements (device_id, timestamp desc);Query the max timestamp first, then locate the record:

sql

create or replace function get_latest_device_measurement(_device_id integer)

returns table (

"timestamp" timestamp,

device_id integer,

value double precision

)

security definer

language sql as

$$

with cte as (

select max(timestamp) from device_measurements

where device_id = _device_id

)

select m.timestamp, m.device_id, m.value

from device_measurements m

join cte on m.timestamp = cte.max

where m.device_id = _device_id

limit 1;

$$;Execution plan shows only one partition scanned. Reports are fast again.

Zero application changes. Zero downtime.

As time goes on, data grows. Crazy, right?

Now we have hundreds of partitions. The query scans only the last partition, but planning time is almost a second. The engine takes too long figuring out what to do.

New approach - query only the physical partition (TimescaleDB chunk) directly:

sql

create or replace function get_latest_device_measurement(_device_id integer)

returns table (

"timestamp" timestamp,

device_id integer,

value double precision

)

security definer

language plpgsql as

$$

declare

_table text;

_record record;

begin

-- Find the latest chunk

select chunk_schema || '.' || chunk_name

into _table

from timescaledb_information.chunks c

where hypertable_schema = 'public'

and hypertable_name = 'device_measurements'

order by range_end desc

limit 1;

-- Query only that chunk

execute format($sql$

with cte as (

select max(timestamp) from %1$s

where device_id = $1

)

select m.timestamp, m.device_id, m.value

from %1$s m

join cte on m.timestamp = cte.max

where m.device_id = $1

limit 1;

$sql$, _table) using _device_id into _record;

return query

select _record.timestamp, _record.device_id, _record.value;

end;

$$;And it works. Latest measurements returned fast. Reports usable again.

The function evolved four times. The implementation went from simple query to CTE to dynamic SQL targeting specific partitions.

The application never changed. Not once.

Zero downtime. Every time.

That's the power of functions as data contracts. When software architects talk about encapsulation and abstraction, they're making a huge mistake when they don't talk about database functions.

And they usually don't.

Security?

This is the principle of least privilege - the same approach militaries use. They call it "need-to-know basis." If you're captured by the enemy, you can't tell them what you don't know.

The military takes security seriously. So should we.

The architecture is simple: two schemas.

sql

-- Private schema: tables and internal functions

create schema data;

create table data.device_measurements (...);

-- Public schema: API functions only

create schema measurements;

-- Application role: can ONLY use the measurements schema

create role app_user login password '***';

grant usage on schema measurements to app_user;That's it. The application connects as app_user, which can only call functions in the measurements schema. No table access. No access to the data schema.

API functions use SECURITY DEFINER to access protected data:

sql

create function measurements.get_latest(_device_id int)

returns table ("timestamp" timestamp, device_id int, value numeric)

security definer -- Runs as the function owner, not the caller

set search_path = pg_catalog, pg_temp -- Protect against search path attacks

language sql as $$

select "timestamp", device_id, value

from data.device_measurements

where device_id = _device_id

order by "timestamp" desc limit 1;

$$;Even if attackers steal your application credentials, they can only call the functions you've exposed. They cannot SELECT * FROM data.device_measurements or dump your tables.

What does this mean for security?

SQL injection becomes structurally impossible. Your application passes parameters to functions. There's no SQL string to inject into.

Data exfiltration requires compromising the database itself. Attackers can only call exposed functions - not access tables directly.

Audit trails are built-in. PostgreSQL can log every function call with parameters.

For a complete authentication example with password hashing, see Database-Level Security.

Performance?

Everyone knows stored procedures are fast. But why and how much?

No Network Round-Trips

javascript

// Traditional: multiple round-trips

const user = await db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = $1', [userId]);

const orders = await db.query('SELECT * FROM orders WHERE user_id = $1', [userId]);

const items = await Promise.all(orders.map(o =>

db.query('SELECT * FROM order_items WHERE order_id = $1', [o.id])

));Dozens of network round-trips. Each adds latency.

sql

-- PostgreSQL function: 1 round-trip

create function api.get_user_with_orders(p_user_id int)

returns jsonb as $$

select jsonb_build_object(

'user', to_jsonb(u),

'orders', (

select jsonb_agg(jsonb_build_object(

'order', to_jsonb(o),

'items', (select jsonb_agg(to_jsonb(oi))

from order_items oi where oi.order_id = o.id)

))

from orders o where o.user_id = u.id

)

)

from users u where u.id = p_user_id;

$$ language sql;Real Benchmark Numbers

From our 2026 benchmark:

| Scenario | NpgsqlRest | Traditional ORMs |

|---|---|---|

| 100 VU, 1 record | 4,588 req/s | 1,700-3,500 req/s |

| 100 VU, 100 records | 377 req/s | 110-330 req/s |

| Pure HTTP overhead | 16,065 req/s | 5,000-9,000 req/s |

That's 2-3x faster than typical ORM-based solutions.

PostgreSQL Does the Heavy Lifting

PostgreSQL's query optimizer has decades of development. It knows your indexes, statistics, and data distribution. Your hand-written application code doesn't.

Maintainability?

Here's a scenario every developer knows:

Users see incorrect data on their dashboard. Bug. Now what?

With functions:

- Connect to PostgreSQL with any query tool

- Call the function:

SELECT * FROM api.get_dashboard_data(123); - Examine the result

Within seconds, you know if the bug is in database logic or frontend. If it's in the function:

sql

-- Fix deployed in seconds, zero downtime

create or replace function api.get_dashboard_data(p_user_id int)

returns jsonb as $$

-- Fixed logic

$$ language sql;No recompilation. No redeployment. No container restarts. No CI/CD pipelines.

Compare to traditional:

- Find the relevant microservice

- Clone repo, set up dev environment

- Track bug across controllers, services, repositories, mappers

- Fix, test, commit, PR, review, merge

- Wait for CI/CD

- Verify in production

Hours or days vs. minutes.

The Black Box Principle

Your database with functions becomes a black box - defined inputs, defined outputs, hidden complexity.

- Multiple applications share the same data layer without duplicating logic

- Schema changes happen behind the interface without breaking clients

- Optimize queries internally without changing the API contract

The device_measurements story demonstrates this perfectly - four completely different implementations, same interface, application never knew.

Zero Boilerplate Code?

This is where NpgsqlRest changes everything.

Traditional REST API:

- Define database schema

- Create entity classes

- Create repository interfaces

- Implement repositories

- Create service classes

- Create DTOs

- Create controllers

- Configure routing

- Add validation

- Handle serialization

With NpgsqlRest:

- Define functions in PostgreSQL

- Done.

sql

-- This IS your API endpoint: POST /api/create-user

create function api.create_user(

p_email text,

p_name text,

p_role text default 'user'

)

returns jsonb as $$

insert into users (email, name, role)

values (p_email, p_name, p_role)

returning jsonb_build_object('id', id, 'email', email, 'name', name);

$$ language sql;NpgsqlRest automatically:

- Creates endpoints from function names

- Maps HTTP methods (

create_= POST,get_= GET) - Validates parameter types

- Serializes responses

- Handles errors

- Respects PostgreSQL security

From our benchmark: 21 lines of configuration vs. 140-350 lines in other frameworks.

"But What About Version Control?"

"While I like postgres functions, the fact that you can change them without touching application code isn't that much of a big advantage. SQL needs to be managed with the same release process as the app."

Fair point. Here's what we do:

Use Flyway, Liquibase, or similar migration tools. Each function goes in a repeatable migration file - one file per function.

When a function changes:

- Edit the repeatable migration file (not the server directly)

- Test locally

- Commit, push, PR, review

- Deploy migration - only that function gets altered

You get version control, code review, and CI/CD - but deployment only updates the changed function. No container restarts, no rolling deployments, no load balancer reconfiguration.

The distinction is: managed change vs. emergency fix. The evolution story was about production optimization without planned downtime. For normal development, use proper migration workflows.

"But What About..."

"ORMs are more productive"

Are they? Count the lines of code. Count the bugs. Count the hours debugging ORM-generated SQL. Count the time on N+1 query problems.

The device_measurements application had N+1 problems that made it sluggish. A function can't fix that (you still need to refactor), but at least you can optimize the individual queries without touching the application.

"SQL is hard to maintain"

SQL is a declarative language designed for data operations. It's been refined for 50 years.

Is it harder to maintain than:

- 17 microservices

- Each with their own ORM configuration

- Duplicated business logic

- Inconsistent data handling

- Complex deployment pipelines

"What about complex business logic?"

PL/pgSQL supports variables, loops, conditionals, exception handling, custom types, table functions, triggers, and procedures for multi-statement transactions.

If your logic is too complex for SQL, ask: is it data logic or application logic? Data logic belongs in the database. Application logic (UI rendering, external API calls, file processing) belongs in your application.

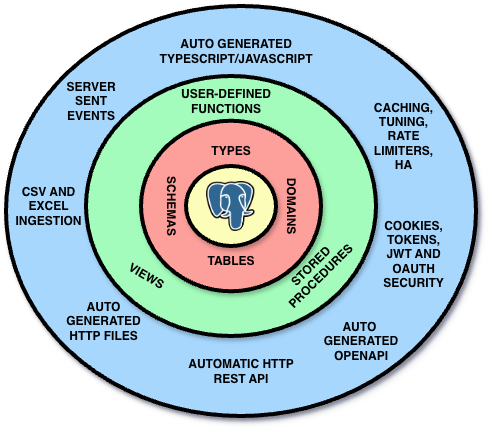

The NpgsqlRest Architecture

NpgsqlRest embraces this philosophy completely. Your PostgreSQL functions are your API.

At the core sits PostgreSQL with its tables, schemas, types, and domains. The next layer - user-defined functions and stored procedures - forms the API boundary. Everything inside is private; the function interface is public.

NpgsqlRest wraps this with:

- Automatic HTTP REST API - Endpoints derived from function signatures

- Auto-generated TypeScript/JavaScript - Type-safe client code

- Auto-generated OpenAPI - Documentation and tooling

- Auto-generated HTTP files - For testing in VS Code/JetBrains

- Server-Sent Events - Real-time streaming from PostgreSQL

- CSV and Excel Ingestion - Upload handling built-in

- Caching, Rate Limiting, HA - Production-ready features

- Cookies, Tokens, JWT, OAuth - Authentication options

All of this from your PostgreSQL schema. No controllers, no services, no repositories, no DTOs, no mappers.

The Code You Don't Write

When your API is defined as PostgreSQL functions, entire application layers disappear:

| Traditional Layer | What It Does | With Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Repository layer | Data access abstraction | Eliminated - functions ARE the abstraction |

| Service layer | Business logic | PostgreSQL functions - logic lives in the database |

| Controller/routes | HTTP handling | Auto-generated from function signatures |

| DTOs/Models | Data transfer objects | Eliminated - function parameters define the contract |

| TypeScript types | Frontend type safety | Auto-generated from function metadata |

| OpenAPI docs | API documentation | Auto-generated from function signatures |

| Validation logic | Input validation | PostgreSQL - type system enforces constraints |

From our benchmark comparison: 21 lines of configuration vs. 140-350 lines in traditional frameworks - for the same functionality.

Real-world validation: One documented project saved ~7,300 lines of code - a 57% reduction in total codebase size.

That's not just less typing. That's:

- Fewer bugs (every line is a potential bug)

- Less maintenance (code you don't write can't break)

- Faster onboarding (less code to understand)

- Smaller attack surface (less code to audit)

Benefits:

- Type safety: PostgreSQL validates all inputs

- Documentation: Function signatures self-document your API

- Versioning: Schema-based (

api_v1.get_user,api_v2.get_user) - Testing: Test functions directly in PostgreSQL

- Debugging: Call functions to reproduce issues

- Performance: One network hop, optimized queries

Conclusion

So, apart from:

- Data Contracts - Formal input/output agreements that survive implementation changes

- Security - SQL injection immunity, least privilege, built-in audit trails

- Performance - 2-3x faster, no N+1 queries, optimized execution plans

- Maintainability - Debug in seconds, fix in place, zero downtime

- Evolvability - Four implementations, same interface, application unchanged

- Code Elimination - 57-95% less code, 7,300+ lines saved in real projects

...what have PostgreSQL functions ever really done for us?

I really don't know.

PostgreSQL functions are Clean Code for your database. Start using them.

More Blog Posts:

Excel Exports Done Right · Passkey SQL Auth · Custom Types & Multiset · Performance & High Availability · Benchmark 2026 · End-to-End Type Checking · Database-Level Security · Multiple Auth Schemes & RBAC · PostgreSQL BI Server · Secure Image Uploads · CSV & Excel Ingestion · Real-Time Chat with SSE · External API Calls · Reverse Proxy & AI Service · Zero to CRUD API · NpgsqlRest vs PostgREST vs Supabase

Get Started:

Quick Start Guide · Benchmark Results · Security Guide · Function Annotations